"Until the killing of black men, black mother's sons

Is as important as the killing of white men, white mothers' sons

We who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes."

Ella Baker began her involvement with the NAACP in 1940. She worked as a field secretary and then served as director of branches from 1943 until 1946.

Inspired by the historic bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955, Baker co-founded the organization "In Friendship" to raise money to fight against Jim Crow Laws in the deep South.

Her influence was reflected in the nickname she acquired: "Fundi," a Swahili word meaning a person who teaches a craft to the next generation. Baker continued to be a respected and influential leader in the fight for human and civil rights until her death on December 13, 1986, her 83rd birthday.

Medgar EversHer influence was reflected in the nickname she acquired: "Fundi," a Swahili word meaning a person who teaches a craft to the next generation. Baker continued to be a respected and influential leader in the fight for human and civil rights until her death on December 13, 1986, her 83rd birthday.

In December of 1954, Evers became the NAACP's first field officer in Mississippi.

After moving to Jackson, he was involved in a boycott campaign against white merchants and was instrumental in eventually desegregating the University of Mississippi when that institution was finally forced to enroll James Meredith in 1962.

In the weeks leading up to his death, Evers found himself the target of a number of threats. His public investigations into the murder of Emmett Till and his vocal support of Clyde Kennard left him vulnerable to attack. On May 28, 1963, a molotov cocktail was thrown into the carport of his home, and five days before his death, he was nearly run down by a car after he emerged from the Jackson NAACP office. Civil rights demonstrations accelerated in Jackson during the first week of June 1963. A local television station granted Evers time for a short speech, his first in Mississippi, where he outlined the goals of the Jackson movement. Following the speech, threats on Evers' life increased.

On June 12, 1963, Evers pulled into his driveway after returning from an integration meeting where he had conferred with NAACP lawyers. Emerging from his car and carrying NAACP T-shirts that stated, "Jim Crow Must Go", Evers was struck in the back with a bullet that ricocheted into his home. He staggered 30 feet before collapsing, dying at the local hospital 50 minutes later. Evers was murdered just hours after President John F. Kennedy's speech on national television in support of civil rights.

As the Pastor of a Baptist Church, an operator of a printing press, and an active member of the NAACP, Reverend George Lee made his mark on the community once referred to as "Bloody Belzoni." He was also the first African-American to register to vote since Reconstruction in Humphreys County, where blacks were a majority of the population. In 1953, Lee and Gus Courts co-founded the Belzoni branch of the NAACP. As early as 1954, Rev. Lee was heavily involved in the local voter registration drives.Working along side Courts, who was elected NAACP president, they successfully registered 92 new African-American voters.

Almost a year after Brown v. Topeka Board of Education and three months before the lynching of Emmett Till in nearby Sunflower County, Reverend George Lee was gunned down in his car on the night of May 7, 1955. When NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers came to investigate the murder, Sheriff Ike Shelton informed him that Lee died from a car crash and that the lead fillings found in his jaw tissues were dental fillings. Shelton insisted that an autopsy was not necessary. An examination of Lee's body by two black physicians revealed that two to three rifle shots were fired, with one puncturing Lee's right rear tire, the other shot fired at point-blank range into the cab, ripping off the lower left side of his face. Rev. Lee staggered from the wreckage, but died shortly thereafter during transportation to the Humphreys County Memorial Hospital.

Rev. Lee's widow, Rosebud Lee, prophetically decided to hold an open-coffin ceremony for her late husband. This decision created a huge media event for black newspapers, planting the seeds for a similar decision by Mamie Till-Mobley, Emmett Till's mother. An additional memorial service organized by the NAACP drew more than one thousand people to this small rural town. Many consider Lee to be the first martyr of the modern Civil Rights Movement.

Rev. Lee's widow, Rosebud Lee, prophetically decided to hold an open-coffin ceremony for her late husband. This decision created a huge media event for black newspapers, planting the seeds for a similar decision by Mamie Till-Mobley, Emmett Till's mother. An additional memorial service organized by the NAACP drew more than one thousand people to this small rural town. Many consider Lee to be the first martyr of the modern Civil Rights Movement.

This case is an early example of what our country is experiencing in 2014:

Although no one was ever convicted for this murder, FBI records reveal that a circumstantial murder case was built against two suspects. However, a local prosecutor refused to take the case to a grand jury. These men, Peck Ray and Joe David Watson Jr., both members of the white Citizen's Council, died in the 1970's.

On May 24, 1961, Jean Thompson (our Amherst community neighbor) was arrested for Breach of Peace after she attempted to integrate a bus station in Jackson, Hinds, Mississippi. Jean was one of 12 Freedom Riders who rode from Montgomery, AL to Jackson. She was one of two women who were part of the ride, along with Rev. CT Vivian, Rev. James Lawson, and Bernard Layfayette.

Politically and socially active, Liuzzo was a member of the Detroit chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. She knew firsthand about the racial injustices that African Americans often suffered in the South, having spent some of her youth in Tennessee and Georgia, among other places. Liuzzo may have been aware of the some of the dangers associated with social activism.

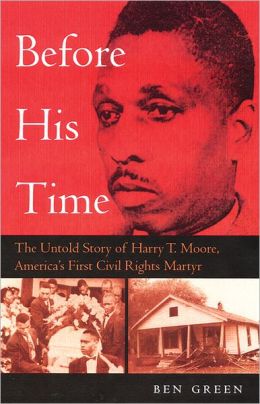

Harry T. Moore, the most hated man in Florida

Harry T. and Harriett V. Moore-- Florida NAACP members who started multiple Branches in that state. Whites, threatened by Moore's voter registration efforts, registering more Black voters that in any other state, bombed the Moore's home on Christmas night 1951. The Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore Memorial Park has been developed to commemorate the lives of two pioneering American black civil rights workers. Harry and Harriette were leading human rights activists in Brevard County, in Florida, and in the nation. They organized the first Brevard County Branch of the NAACP in 1934, and he led the Florida organization and the fight for equality and justice until their deaths. As executive secretary of the Progressive Voters League, he helped break down registration barriers and was responsible for the registration of tens of thousands of black Americans throughout Florida.

They were murdered in their home in Mims when a bomb was exploded under their bedroom on Christmas evening, 1951, their 25th wedding anniversary. It was the first killing of a prominent civil rights leader, and was a spark that ignited the American civil rights movement.Harry T. Moore is remembered by his students for his dignity, his determination, his compassion, his discipline, and the great value he placed on education. He is remembered by those with whom he worked, as a gentleman of learning, ethics, courage and persistence; who had a deep appreciation for the values that make America great. Harry Moore was the first NAACP official killed in the civil rights struggle, and he and Harriette are the only husband and wife to give their lives to the movement.

Freedom Never Dies: The Legacy of Harry T. Moore

This PBS film with teaching resources, explores the life and times of this enigmatic leader, a distinguished school teacher whose passionate crusade for equal rights could not be discouraged by either the white power structure or the more cautious factions of his own movement. Although Moore's assassination was an international cause celebre in 1951, it was overshadowed by following events and eventually almost forgotten.

In 1934, Harry Moore started the Brevard County NAACP, and steadily built it into a formidable organization. In 1937, in conjunction with the all-black Florida State Teacher's Association, and backed by the NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall in New York, Moore filed the first lawsuit in the Deep South to equalize black and white teacher salaries. His good friend, John Gilbert, principal of the Cocoa Junior High School, courageously volunteered as the plaintiff. Although the Gilbert case was eventually lost in state court, it spawned a dozen other federal lawsuits in Florida that eventually led to equalized salaries.

Ida Barnett Wells a fearless anti-lynching crusader, suffragist, women's rights advocate, journalist, and speaker. She stands as one of our nation's most uncompromising leaders and most ardent defenders of democracy.

It was the rise of lynching that put Black women at the center of anti-racist work. Although the largest number of victims were young Black men accused of raping white women, Black women like Ida B. Wells—who led the first anti-lynching campaign back in 1892—pointed out that Black women were lynched too, and that the stereotypes of hypersexuality and immorality that were getting Black men killed were deeply connected to stereotypes of Black women that kept them vulnerable to sexual predation and devalued them as persons. With the understanding that racial violence against men was also a women’s issue, and that violence against women was both a race and gender issue, Black women made anti-lynching activism a central tenet of their organizations long before the NAACP was founded.

An

important part of black women's contribution to the NAACP campaign for the Dyer

Bill was the establishment of an organization that publicized the horrors of

lynching and provided a focus for campaign fundraising. The Anti-Lynching

Crusaders, founded in 1922 under the aegis of the NAACP, was a women's

organization that aimed to raise money to promote the passage of the Dyer Bill

and for the prevention of lynching in general.

This ad was part of an NAACP effort to lobby Congress to pass the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill. The bill passed easily in the House of Representatives but never came to a vote in the Senate because of filibusters in 1922, 1923 and 1924. Source: New York Times, November 23, 1922—American Social History Project.

| "A Man Was Lynched Yesterday" | |

A Man Was Lynched Yesterday. Flag flying above Fifth Avenue, New York City, ca. 1938. Copyprint. NAACP Collection, Prints and Photographs Division. Reproduction Number: LC-USZC4-4734/LC-USZ62-33793 (6-10b) Courtesy of the NAACP | |

| At its headquarters, 69 Fifth Avenue, New York City, the NAACP flew a flag to report lynchings, until, in 1938, the threat of losing its lease forced the association to discontinue the practice. | |

A little more than 100 years ago, in the midst of a two-day riot, 5,000 spectators gathered in Springfield, Ill., to witness the lynching of two African-American men. Incited partly by a false rape accusation, mobs torched black-owned businesses and buildings, forcing 2,000 African Americans to permanently flee the city. That such hatred would exhibit itself in Abraham Lincoln's hometown just six months before his 100th birthday made the news even more appalling.