On Nov. 5, 2016 Ernie Dalkas wrote:

On Sept. 26, 2016 Dorothy Cresswell wrote:

To my Amherst Community,

Dear

President Obama:

Because this Veterans Day will be your last as Commander and

Chief, I want to tell you about an exceptional group of girls.

These girls are members of the Amherst Massachusetts

Regional High School Varsity Volleyball team.

It is not their 20-0-0 record or their rankings of 3rd in the

state and 219 in the nation that is impressive.

It is how these girls conduct themselves off the court that is

inspiring. When faced with what first

appears to be opposite political positions, these girls united and stood

together as one team.

I am honored to tell you their story.

Recently, I was approached by the coach of the girls’ volleyball

team. Because my daughter played on the

Junior Varsity team and I am a veteran, she was concerned I might have been

offended by the actions of the Varsity girls.

During the playing of our National Anthem, all but one of these girls

took a knee with hands on hearts to support Black Lives Matter.

I assured her I was not offended and in fact I believe the

girl’s actions had honored our Veterans.

After explaining my reasoning, she invited me to speak to the girls and

I told them the following story.

When I joined the Marine Corp in 1967 I took an oath to defend

the Constitution. I was sent to Vietnam

and served with the 1st Reconnaissance Battalion.

My reconnaissance team conducted classified covert missions,

operating in the jungle, deep inside enemy territory. The team consisted of as few as three Marines. Contact with the enemy was often made at ten

feet or less. The team survival depended

on each Marine doing his job.

In a way, the girls’ volleyball team is like a reconnaissance

team. While their mission is different,

their success depends on every team member doing her job.

During the playing of our National Anthem, it took courage

for these girls to proudly take a knee in support of Black Lives Matter. It took even greater courage for one girl to

proudly stand.

Did these differing political views show a division within

the team? The answer is a resounding no! These girls united as a team. They linked together by holding hands. They demonstrated that above all, they are a

team.

Most people know that on November 11, America celebrates

Veterans Day. What most people do not

know is that on November 10, the Marine Corps celebrates it’s 241st birthday.

Because of these upcoming events, I was

honored to tell the Varsity girls the story of a true American Hero, PFC

Johnson.

PFC Johnson was a 19-year-old African American Marine who

gave his life in service to our country and more importantly, for his team, his

friends. Even though he may be long forgotten,

his family, and his Marine brothers and sisters will forever remember him. We Marines share a bond deeply rooted in

history and tradition.

His story is best told by the following Citation.

The President of the United States

In the name of the Congress of the of the United States

Takes pride in presenting the

MEDAL OF HONOR

posthumously to

RALPH HENRY JOHNSON

Private First Class

United States Marine Corps

Citation:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his

life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as a reconnaissance scout

with Company A, in action against the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong

forces. In the early morning hours

during Operation ROCK, PFC Johnson was a member of a 15-man reconnaissance

patrol manning an observation post on Hill 146 overlooking the Quan Duc Valley

deep in enemy controlled territory. They

were attacked by a platoon-size hostile force employing automatic weapons,

satchel charges and hand grenades.

Suddenly, a hand grenade landed in the 3-man fighting hole occupied by

PFC Johnson and 2 fellow marines.

Realizing the inherent danger to his 2 comrades, he shouted a warning

and unhesitatingly hurled himself upon the explosive device. When the grenade exploded, PFC Johnson absorbed

the tremendous impact of the blast and was killed instantly. His prompt and heroic act saved the life of 1

marine at the cost of his life and undoubtedly prevented the enemy from

penetrating his sector of the patrol’s perimeter. PFC Johnson’s courage, inspiring valor and

selfless devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the

Marine Corps and the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.

When we join the military, we take an oath to defend the

Constitution. I believe the most

important Freedom granted under the Constitution is Freedom

of Speech.

PFC Johnson gave his life defending our Constitution. What better way to honor his sacrifice and

the sacrifices of all our veterans, past, present, and future, than to

peacefully exercise our right of Freedom of Speech?

There are many reasons America should be proud of PFC

Johnson and the Amherst girls’ Varsity Volleyball team. The most important reason is they are a shining example of what it truly means

to be an American. It is often the

young who teach us the most important lessons of life.

We as American need to follow their example. We cannot let our differences destroy

us. We need to remember that as

Americans, we are a team. We need to

hold hands and act as a team. For when

we do, we achieve great things.

Simper Fi,

Ernest J.

Dalkas

Sgt. USMC

(Ret.)

On Sept. 26, 2016 Dorothy Cresswell wrote:

To my Amherst Community,

This morning I sit down to write from my heart. My white, privileged, troubled, sad heart. I can hardly bear the news lately, but I must watch these videos and read the accounts because this stuff is real and true for so many whose lives are precious. Whose souls and families and hopes and hurts MATTER.

I want to scream and arrest every one of those police officers who harassed that poor man with a traumatic brain injury who was sitting in his car minding his own business, being a good parent waiting for the school bus. But they surrounded him, pointed their guns at him, yelled at him, and when, not knowing what else to do the poor guy got out of the car and walked away from these frightening people, shot him down. In the back. As he laid on the ground dying, maybe even already dead, still holding a gun beamed on him, they dramatically called for and applied handcuffs.

This is not police protection. This is downright gang murder. I cannot comprehend the reasoning that led them to even begin this encounter much less to escalate it to killing the man.

I CAN comprehend the outrage and need to come out in the streets and scream the pain and heartache.

With them I cry for this to stop and for justice. This was a lynching. Singling out a man who was doing no harm to anyone. What gave them the right to disturb him, much less to kill him????

I shudder and grieve for the souls of all of us who live in such a time as this. What can we do? We don’t know the next place this kind of encounter will pop up, or we could rally round and stand and question BEFORE the gun goes off.

I saw an amazing video of an encounter in another country where instead of carrying guns, the police carried shields. And instead of shooting a man who was swinging a machete endangering all, repeatedly approaching the police swinging the machete, the police paused, held up their shields to protect themselves, and walked their circle in, protecting themselves and the public and not harming the troubled soul. Not one person’s life was taken. Not one person was even hurt. The people taking that video talked about how sad the man looked, that something must have happened to him, that they really respected the police and how frightening it must have been to have this man swinging at them, but how they really handled it well.

Dorothy Cresswell

Keep singing, keep looking up, keep asking questions, and never give up!

I Am Afraid I Will Be KILLED By Police, Video by KevOnStage

Friday, August, 7, 2015

Gary and Carlie Tartakov: More work needed on race relations

That was surely the case in the July 11 edition of the Gazette with the announcement of the settlement of the suit against the Amherst School District and the posting of the Confederate flags in Williamsburg.

There has been a good deal of controversy over the Amherst School District’s handling of the racial harassment of its math teacher, Carolyn Gardner, last year. There is no doubt that people in the school and in the town were disturbed by the multiple appearances of racist graffiti and the note alluding to bringing a gun to school. There were outpourings of sympathy from people in town and statements by the school administration condemning the acts and declaring their intention to find who was responsible.

And the issue went on for some time, as there was what seemed like the tampering with her classroom chair that collapsed from the removal of screws and then the flattening of a tire on her car. The culprits were never found.

Then there was another sort of controversy over the teacher’s not finishing the year due to stress she suffered from these incidents and what she declared in a statement to the school board was the school administration’s “anemic” response to her situation.

On one side there were people lining up to show support for Gardner and on the other there were some concerned to defend the school system from what they saw as suggestions of racism in the lack of a response.

The controversy in town grew when the teacher and the school system failed to come to an agreement about her assignment for the following year and she filed a complaint with the state Commission Against Discrimination, which was concluded with arbitration in March.

It was the result of the arbitration that was announced in May and revealed in a front-page article in the Gazette July 11, next to a separate article on the subject of the Confederate flag being raised over a local business in protest of the removal of the Confederate flag from beside the State House in South Carolina.

Ours is a region of the state and the country that many see as liberal and others as overly so. Some are glad for the presence of African Americans among us and having teachers like Gardner, who was praised for her teaching of math at Northampton High School for many years before she moved to teach in Amherst.

Three years back, people in Amherst reconstituted its NAACP chapter as a step towards getting the school district to enforce the court-ordered training of its staff on racial issues, which it had been ignoring since the mid-1990s. That issue hasn’t been settled yet.

None of the issues in the Amherst schools takes on the horrifying gravity of the terrorist murders at the church in South Carolina or the rioting in Missouri over the gross mistreatment of the people of color in the city of Fergusson.

A good percentage of our citizens believe we should focus on the progress the U.S. has made over the years since the ending of federal government support of Jim Crow discrimination and persecution of blacks that came with the Civil Rights laws of the 1960s. But African Americans continue to be persecuted in life-blighting and life-threatening ways.

Some of us think enough has been done already and we ought to get beyond fussing over what seem to them like petty issues and incidents. But there are those of us who see that traditions, like raising the Confederate flag or threatening a teacher in the high school on the basis of her being a black woman, as reminders that we still have a long way to go. And maybe just asking her to get over it, or take another assignment at the district’s convenience may not be a good enough way to do that.

The fact that the school district felt it necessary to pay Gardner what amounts to two years salary and lawyer’s costs in order to get her to suspend her suit against them for discrimination says that they were forced to recognize the merit of her complaint. The funds are little more than what it will likely cost for her to search for another job and move her family to a safer place.

Our local progress on race issues can be measured today by those two front-page issues. The numbers of whites who showed up with Latinas, Cambodians, blacks and others to support Gardner in her struggle to live and work in Amherst show how far we have come in our effort to make this an American community that values all its citizens.

The number of those who dismiss her feelings of being threatened — in this place where they feel so safe they can’t understand what she has to complain about — show how far we still have to go.

Gary Tartakov and Carlie Tartakov are longtime residents of Amherst.

Week of December 1, 2014

Ferguson isn’t about black rage against cops. It’s white rage against progress.

By Carol Anderson

Tim Wise: Most white people in America are completely oblivious Tim Wise, AlterNet 27 Nov 2014 at 07:29 ET

Demonstrators put their hands in the air during a protest against the shooting death of Michael Brown, as police officers (unseen) point their weapons at them in Ferguson, Missouri August 18, 2014. REUTERS/Joshua Lott

Don't miss stories. Follow Raw Story!

Black people have to learn everything about white people just to stay alive. White people just don’t get that.

This story first appeared at AlterNet.

I suppose there is no longer much point in debating the facts surrounding the shooting of Michael Brown. First, because Officer Darren Wilson has been cleared by a grand jury, and even the collective brilliance of a thousand bloggers pointing out the glaring inconsistencies in his version of events that August day won’t result in a different outcome. And second, because Wilson’s guilt or innocence was always somewhat secondary to the larger issue: namely, the issue of this gigantic national inkblot staring us in the face, and what we see when we look at it—and more to the point, why?

Not to overdo the medical metaphors, but as with those other cases noted above, so too in this one did a disturbing number of whites manifest something of a repetitive motion disorder—a reflex nearly as automatic as the one that leads so many police (or wanna-be police) to fire their weapons at black men in the first place. It is a reflex to rationalize the event, defend the shooter, trash the dead with blatantly racist rhetoric and imagery, and then deny that the incident or one’s own response to it had anything to do with race.

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial about sending around those phony pictures claimed to be of Mike Brown posing with a gun, or the one passed off as Darren Wilson in a hospital bed with his orbital socket blown out.

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial about how quickly those pictures were believed to be genuine by so many who distributed them on social media, even when they weren’t, and how difficult it is for some to discern the difference between one black man and another.

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial about how rapidly many bought the story that Wilson had been attacked and bloodied, even as video showed him calmly standing at the scene of the shooting without injury, and even as the preliminary report on the incident made no mention of any injuries to Officer Wilson, and even as Wilson apparently has a history of power-tripping belligerence towards those with whom he interacts, and a propensity to distort the details of those encounters as well.

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial about Cardinals fans taunting peaceful protesters who gathered outside a playoff game to raise the issue of Brown’s death, by calling them crackheads or telling them that it was only because of whites that blacks have any freedoms at all, or that they should “get jobs” or “pull up their pants,” or go back to Africa.

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial about sending money to Darren Wilson’s defense fund and then explaining one’s donation by saying what a service the officer had performed by removing a “savage” like Brown from the community, or by referring to Wilson’s actions as “animal control.”

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial about reaction to evidence of weed in Brown’s lifeless body, as with Trayvon’s before him, even though whites use drugs at the same rate as blacks, but rarely have that fact offered up as a reason for why we might deserve to be shot by police.

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial behind the belief that the head of the Missouri Highway Patrol, brought in to calm tensions in Ferguson, was throwing up gang signs on camera, when actually, it was a hand sign for the black fraternity of which that officer is a member; and to deny that there is anything racial about one’s stunning ignorance as to the difference between those two things.

Reflex: To deny that there’s anything at all racial about the way that even black victims of violence—like Brown, like Trayvon Martin, and dozens of others—are often spoken of more judgmentally than even the most horrific of white perpetrators, the latter of whom are regularly referred to as having been nice, and quiet, and smart, and hardly the type to kill a dozen people, or cut them into little pieces, or eat their flesh after storing it in the freezer for several weeks.

And most of all, the reflex to deny that there is anything racial about the lens through which we typically view law enforcement; to deny that being white has shaped our understanding of policing and their actions in places like Ferguson, even as being white has had everything to do with those matters. Racial identity shapes the way we are treated by cops, and as such, shapes the way we are likely to view them. As a general rule, nothing we do will get us shot by law enforcement: not walking around in a big box store with semi-automatic weapons (though standing in one with an air rifle gets you killed if you’re black); not assaulting two officers, even in the St. Louis area, a mere five days after Mike Brown was killed; not pointing a loaded weapon at three officers and demanding that they—the police—”drop their fucking guns;” not committing mass murder in a movie theatre before finally being taken alive; not proceeding in the wake of that event to walk around the same town in which it happened carrying a shotgun; and not killing a cop so as to spark a “revolution,” and then leading others on a two month chase through the woods before being arrested with only a few scratches.

To white America, in the main, police are the folks who help get our cats out of the tree, or who take us on ride-arounds to show us how gosh-darned exciting it is to be a cop. We experience police most often as helpful, as protectors of our lives and property. But that is not the black experience by and large; and black people know this, however much we don’t. The history of law enforcement in America, with regard to black folks, has been one of unremitting oppression. That is neither hyperbole nor opinion, but incontrovertible fact. From slave patrols to overseers to the Black Codes to lynching, it is a fact. From dozens of white-on-black riots that marked the first half of the 20th century (in which cops participated actively) to Watts to Rodney King to Abner Louima to Amadou Diallo to the railroading of the Central Park 5, it is a fact. From the New Orleans Police Department’s killings of Adolph Archie to Henry Glover to the Danziger Bridge shootings there in the wake of Katrina to stop-and-frisk in places like New York, it’s a fact. And the fact that white people don’t know this history, have never been required to learn it, and can be considered even remotely informed citizens without knowing it, explains a lot about what’s wrong with America. Black people have to learn everything about white people just to stay alive. They especially and quite obviously have to know what scares us, what triggers the reptilian part of our brains and convinces us that they intend to do us harm. Meanwhile, we need know nothing whatsoever about them. We don’t have to know their history, their experiences, their hopes and dreams, or their fears. And we can go right on being oblivious to all that without consequence. It won’t be on the test, so to speak.

I think this, more than anything, is the source of our trouble when it comes to racial division in this country. The inability of white people to hear black reality—to not even know that there is one and that it differs from our own—makes it nearly impossible to move forward. But how can we expect black folks to trust law enforcement or to view it in the same heroic and selfless terms that so many of us apparently do? The law has been a weapon used against black bodies, not a shield intended to defend them, and for a very long time.

In his contribution to Jill Nelson’s 2000 anthology on police brutality, scholar Robin D.G Kelley reminds us of the bill of particulars.* As Kelley notes, in colonial Virginia, slave owners were allowed to beat, burn, and even mutilate slaves without fear of punishment; and throughout the colonial period, police not only looked the other way at the commission of brutality against black folks, but were actively engaged in the forcible suppression of slave uprisings and insurrections. Later, after abolition, law enforcement regularly and repeatedly released black prisoners into the hands of lynch mobs and stood by as their bodies were hanged from trees, burned with blowtorches, body parts amputated and given out as souvenirs. In city after city, north and south, police either stood by or actively participated in pogroms against African American communities: in Wilmington, North Carolina, Atlanta, New Orleans, New York City, Akron and Birmingham, just to name a few. In one particularly egregious anti-black rampage in East St. Louis, Illinois, in 1917, police shot blacks dead in the street as part of an orgy of violence aimed at African Americans who had moved from the Deep South in search of jobs. One hundred and fifty were killed, including thirty-nine children whose skulls were crushed and whose bodies were thrown into bonfires set by white mobs. In the 1920s, it is estimated that half of all black people who were killed by whites, were killed by white police officers.

But Kelley continues: In 1943 white police in Detroit joined with others of their racial compatriots, attacking blacks who had dared to move into previously all-white public housing, killing seventeen. In the 1960s and early ’70s police killed over two dozen members of the Black Panther Party, including those like Mark Clark and Fred Hampton in Chicago, asleep in their beds at the time their apartment was raided. In 1985, Philadelphia law enforcement perpetrated an all-out assault on members of the MOVE organization, bombing their row houses from state police helicopters, killing eleven, including five children, destroying sixty-one homes and leaving hundreds homeless.

These are but a few of the stories one could tell, and which Kelley does in his extraordinary recitation of the history—and for most whites, we are without real knowledge of any of them. But they and others like them are incidents burned into the cell memory of black America. They haven’t the luxury of forgetting, even as we apparently cannot be bothered to remember, or to learn of these things in the first place. Bull Connor, Sheriff Jim Clark, Deputy Cecil Price: these are not far-away characters for most black folks. How could they be? After all, more than a few still carry the scars inflicted by men such as they. And while few of us would think to ridicule Jews for still harboring less than warm feelings for Germans some seventy years later—we would understand the lack of trust, the wariness, even the anger—we apparently find it hard to understand the same historically-embedded logic of black trepidation and contempt for law enforcement in this country. And this is so, even as black folks’ negative experiences with police have extended well beyond the time frame of Hitler’s twelve year Reich, and even as those experiences did not stop seventy years ago, or even seventy days ago, or seventy minutes.

Can we perhaps, just this once, admit our collective blind spot? Admit that there are things going on, and that have been going on a very long time, about which we know nothing? Might we suspend our disbelief, just long enough to gain some much needed insights about the society we share? One wonders what it will take for us to not merely listen but actually to hear the voices of black parents, fearful that the next time their child walks out the door may be the last, and all because someone—an officer or a self-appointed vigilante—sees them as dangerous, as disrespectful, as reaching for their gun? Might we be able to hear that without deftly pivoting to the much more comfortable (for us) topic of black crime or single-parent homes? Without deflecting the real and understandable fear of police abuse with lectures about the danger of having a victim mentality—especially ironic given that such lectures come from a people who apparently see ourselves as the always imminent victims of big black men?

Can we just put aside all we think we know about black communities (most of which could fit in a thimble, truth be told) and imagine what it must feel like to walk through life as the embodiment of other people’s fear, as a monster that haunts their dreams the way Freddie Kreuger does in the movies? To be the physical representation of what marks a neighborhood as bad, a school as bad, not because of anything you have actually done, but simply because of the color of your skin? Surely that is not an inconsequential weight to bear. To go through life, every day, having to think about how to behave so as not to scare white people, or so as not to trigger our contempt—thinking about how to dress, and how to walk and how to talk and how to respond to a cop (not because you’re wanting to be polite, but because you’d like to see your mother again)—is work; and it’s harder than any job that any white person has ever had in this country. To be seen as a font of cultural contagion is tantamount to being a modern day leper.

And then perhaps we might spend a few minutes considering what this does to the young black child, and how it differs from the way that white children grow up. Think about how you would respond to the world if that world told you every day how awful you were, how horrible your community was, and how pathological your family. That’s what we’re telling black people daily. Every time police call the people they are sworn to protect animals, as at least one Ferguson officer was willing to do on camera, we tell them this. Every time we shrug at the way police routinely stop and frisk young black men, we tell them this. Every time we turn away from the clear disparities in our nation’s schools, which relegate the black and brown to classrooms led by the least experienced teachers, we tell them this. Every time Bill O’Reilly pontificates about “black culture” and every time Barack Obama tells black men to be better fathers, we tell them this: that they are uniquely flawed, uniquely pathological, a cancerous mass of moral decrepitude to be feared, scorned, surveilled, incarcerated and discarded. The constant drumbeat of negativity is so normalized by now that it forms the backdrop of every conversation about black people held in white spaces when black folks themselves are not around. It is like the way your knee jumps when the doctor taps it with that little hammer thing during a check-up: a reflex by now instinctual, automatic, unthinking.

And still we pretend that one can think these things—that vast numbers of us can—and yet be capable of treating black folks fairly in the workforce, housing market, schools or in the streets; that we can, on the one hand, view the larger black community as a chaotic maelstrom of iniquity, while still managing, on the other, to treat black loan applicants, job applicants, students or random strangers as mere individuals. That we can somehow thread the needle between our grand aspirations to equanimity as Americans and our deeply internalized biases regarding broad swaths of our nation’s people.

But we can’t; and it is in these moments—moments like those provided by events in Ferguson—that the limits of our commitment to that aspirational America are laid bare. It is in moments like these when the chasm between our respective understandings of the world—itself opened up by the equally cavernous differences in the way we’ve experienced it—seems almost impossible to bridge. But bridge them we must, before the strain of our repetitive motion disorder does permanent and untreatable damage to our collective national body.

_____

*Robin D.G. Kelley, “Slangin’ Rocks…Palestinian Style,” in Police Brutality: An Anthology, Jill Nelson, ed., (New York, W. W. Norton, 2000), 21-59.

Tim Wise is the author of six books on race, including White Like Me: Reflections on Race from a Privileged Son and Dear White America: Letter to a New Minority. His website is timwise.org and he tweets @timjacobwise.

This story first appeared at AlterNet.

I suppose there is no longer much point in debating the facts surrounding the shooting of Michael Brown. First, because Officer Darren Wilson has been cleared by a grand jury, and even the collective brilliance of a thousand bloggers pointing out the glaring inconsistencies in his version of events that August day won’t result in a different outcome. And second, because Wilson’s guilt or innocence was always somewhat secondary to the larger issue: namely, the issue of this gigantic national inkblot staring us in the face, and what we see when we look at it—and more to the point, why?

Because it is a kind of racial Rorschach (is it not?) into which each of these cases—not just Brown but all the others, from Trayvon Martin to Sean Bell to Patrick Dorismond to Aswan Watson and beyond—inevitably and without fail morph. That we see such different things when we look upon them must mean something. That so much of white America cannot see the shapes made out so clearly by most of black America cannot be a mere coincidence, nor is it likely an inherent defect in our vision. Rather, it is a socially-constructed astigmatism that blinds so many to the way in which black folks often experience law enforcement.

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial about sending around those phony pictures claimed to be of Mike Brown posing with a gun, or the one passed off as Darren Wilson in a hospital bed with his orbital socket blown out.

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial about how quickly those pictures were believed to be genuine by so many who distributed them on social media, even when they weren’t, and how difficult it is for some to discern the difference between one black man and another.

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial about how rapidly many bought the story that Wilson had been attacked and bloodied, even as video showed him calmly standing at the scene of the shooting without injury, and even as the preliminary report on the incident made no mention of any injuries to Officer Wilson, and even as Wilson apparently has a history of power-tripping belligerence towards those with whom he interacts, and a propensity to distort the details of those encounters as well.

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial about Cardinals fans taunting peaceful protesters who gathered outside a playoff game to raise the issue of Brown’s death, by calling them crackheads or telling them that it was only because of whites that blacks have any freedoms at all, or that they should “get jobs” or “pull up their pants,” or go back to Africa.

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial about sending money to Darren Wilson’s defense fund and then explaining one’s donation by saying what a service the officer had performed by removing a “savage” like Brown from the community, or by referring to Wilson’s actions as “animal control.”

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial about reaction to evidence of weed in Brown’s lifeless body, as with Trayvon’s before him, even though whites use drugs at the same rate as blacks, but rarely have that fact offered up as a reason for why we might deserve to be shot by police.

Reflex: To deny that there was anything racial behind the belief that the head of the Missouri Highway Patrol, brought in to calm tensions in Ferguson, was throwing up gang signs on camera, when actually, it was a hand sign for the black fraternity of which that officer is a member; and to deny that there is anything racial about one’s stunning ignorance as to the difference between those two things.

Reflex: To deny that there’s anything at all racial about the way that even black victims of violence—like Brown, like Trayvon Martin, and dozens of others—are often spoken of more judgmentally than even the most horrific of white perpetrators, the latter of whom are regularly referred to as having been nice, and quiet, and smart, and hardly the type to kill a dozen people, or cut them into little pieces, or eat their flesh after storing it in the freezer for several weeks.

And most of all, the reflex to deny that there is anything racial about the lens through which we typically view law enforcement; to deny that being white has shaped our understanding of policing and their actions in places like Ferguson, even as being white has had everything to do with those matters. Racial identity shapes the way we are treated by cops, and as such, shapes the way we are likely to view them. As a general rule, nothing we do will get us shot by law enforcement: not walking around in a big box store with semi-automatic weapons (though standing in one with an air rifle gets you killed if you’re black); not assaulting two officers, even in the St. Louis area, a mere five days after Mike Brown was killed; not pointing a loaded weapon at three officers and demanding that they—the police—”drop their fucking guns;” not committing mass murder in a movie theatre before finally being taken alive; not proceeding in the wake of that event to walk around the same town in which it happened carrying a shotgun; and not killing a cop so as to spark a “revolution,” and then leading others on a two month chase through the woods before being arrested with only a few scratches.

To white America, in the main, police are the folks who help get our cats out of the tree, or who take us on ride-arounds to show us how gosh-darned exciting it is to be a cop. We experience police most often as helpful, as protectors of our lives and property. But that is not the black experience by and large; and black people know this, however much we don’t. The history of law enforcement in America, with regard to black folks, has been one of unremitting oppression. That is neither hyperbole nor opinion, but incontrovertible fact. From slave patrols to overseers to the Black Codes to lynching, it is a fact. From dozens of white-on-black riots that marked the first half of the 20th century (in which cops participated actively) to Watts to Rodney King to Abner Louima to Amadou Diallo to the railroading of the Central Park 5, it is a fact. From the New Orleans Police Department’s killings of Adolph Archie to Henry Glover to the Danziger Bridge shootings there in the wake of Katrina to stop-and-frisk in places like New York, it’s a fact. And the fact that white people don’t know this history, have never been required to learn it, and can be considered even remotely informed citizens without knowing it, explains a lot about what’s wrong with America. Black people have to learn everything about white people just to stay alive. They especially and quite obviously have to know what scares us, what triggers the reptilian part of our brains and convinces us that they intend to do us harm. Meanwhile, we need know nothing whatsoever about them. We don’t have to know their history, their experiences, their hopes and dreams, or their fears. And we can go right on being oblivious to all that without consequence. It won’t be on the test, so to speak.

We can remain ignorant to the ubiquity of police misconduct, thinking it the paranoid fever dream of irrational “race-card” playing peoples of color, just like we did after the O.J. Simpson verdict. When most of black America responded to that verdict with cathartic relief—not because they necessarily thought Simpson innocent but because they felt there were enough questions raised about police in the case to sow reasonable doubt—most white folks concluded that black America had lost its collective mind. How could they possibly believe that the LAPD would plant evidence in an attempt to frame or sweeten the case against a criminal defendant? A few years later, had we been paying attention (but of course, we were not), we would have had our answer. It was then that the scandal in the city’s Ramparts division broke, implicating dozens of police in over a hundred cases of misconduct, including, in one incident, shooting a gang member at point blank range and then planting a weapon on him to make the incident appear as self-defense. So putting aside the guilt or innocence of O.J,, clearly it was not irrational for black Angelenos (and Americans) to give one the likes of Mark Fuhrman side-eye after his own racism was revealed in that case.

In his contribution to Jill Nelson’s 2000 anthology on police brutality, scholar Robin D.G Kelley reminds us of the bill of particulars.* As Kelley notes, in colonial Virginia, slave owners were allowed to beat, burn, and even mutilate slaves without fear of punishment; and throughout the colonial period, police not only looked the other way at the commission of brutality against black folks, but were actively engaged in the forcible suppression of slave uprisings and insurrections. Later, after abolition, law enforcement regularly and repeatedly released black prisoners into the hands of lynch mobs and stood by as their bodies were hanged from trees, burned with blowtorches, body parts amputated and given out as souvenirs. In city after city, north and south, police either stood by or actively participated in pogroms against African American communities: in Wilmington, North Carolina, Atlanta, New Orleans, New York City, Akron and Birmingham, just to name a few. In one particularly egregious anti-black rampage in East St. Louis, Illinois, in 1917, police shot blacks dead in the street as part of an orgy of violence aimed at African Americans who had moved from the Deep South in search of jobs. One hundred and fifty were killed, including thirty-nine children whose skulls were crushed and whose bodies were thrown into bonfires set by white mobs. In the 1920s, it is estimated that half of all black people who were killed by whites, were killed by white police officers.

But Kelley continues: In 1943 white police in Detroit joined with others of their racial compatriots, attacking blacks who had dared to move into previously all-white public housing, killing seventeen. In the 1960s and early ’70s police killed over two dozen members of the Black Panther Party, including those like Mark Clark and Fred Hampton in Chicago, asleep in their beds at the time their apartment was raided. In 1985, Philadelphia law enforcement perpetrated an all-out assault on members of the MOVE organization, bombing their row houses from state police helicopters, killing eleven, including five children, destroying sixty-one homes and leaving hundreds homeless.

These are but a few of the stories one could tell, and which Kelley does in his extraordinary recitation of the history—and for most whites, we are without real knowledge of any of them. But they and others like them are incidents burned into the cell memory of black America. They haven’t the luxury of forgetting, even as we apparently cannot be bothered to remember, or to learn of these things in the first place. Bull Connor, Sheriff Jim Clark, Deputy Cecil Price: these are not far-away characters for most black folks. How could they be? After all, more than a few still carry the scars inflicted by men such as they. And while few of us would think to ridicule Jews for still harboring less than warm feelings for Germans some seventy years later—we would understand the lack of trust, the wariness, even the anger—we apparently find it hard to understand the same historically-embedded logic of black trepidation and contempt for law enforcement in this country. And this is so, even as black folks’ negative experiences with police have extended well beyond the time frame of Hitler’s twelve year Reich, and even as those experiences did not stop seventy years ago, or even seventy days ago, or seventy minutes.

Can we perhaps, just this once, admit our collective blind spot? Admit that there are things going on, and that have been going on a very long time, about which we know nothing? Might we suspend our disbelief, just long enough to gain some much needed insights about the society we share? One wonders what it will take for us to not merely listen but actually to hear the voices of black parents, fearful that the next time their child walks out the door may be the last, and all because someone—an officer or a self-appointed vigilante—sees them as dangerous, as disrespectful, as reaching for their gun? Might we be able to hear that without deftly pivoting to the much more comfortable (for us) topic of black crime or single-parent homes? Without deflecting the real and understandable fear of police abuse with lectures about the danger of having a victim mentality—especially ironic given that such lectures come from a people who apparently see ourselves as the always imminent victims of big black men?

Can we just put aside all we think we know about black communities (most of which could fit in a thimble, truth be told) and imagine what it must feel like to walk through life as the embodiment of other people’s fear, as a monster that haunts their dreams the way Freddie Kreuger does in the movies? To be the physical representation of what marks a neighborhood as bad, a school as bad, not because of anything you have actually done, but simply because of the color of your skin? Surely that is not an inconsequential weight to bear. To go through life, every day, having to think about how to behave so as not to scare white people, or so as not to trigger our contempt—thinking about how to dress, and how to walk and how to talk and how to respond to a cop (not because you’re wanting to be polite, but because you’d like to see your mother again)—is work; and it’s harder than any job that any white person has ever had in this country. To be seen as a font of cultural contagion is tantamount to being a modern day leper.

And then perhaps we might spend a few minutes considering what this does to the young black child, and how it differs from the way that white children grow up. Think about how you would respond to the world if that world told you every day how awful you were, how horrible your community was, and how pathological your family. That’s what we’re telling black people daily. Every time police call the people they are sworn to protect animals, as at least one Ferguson officer was willing to do on camera, we tell them this. Every time we shrug at the way police routinely stop and frisk young black men, we tell them this. Every time we turn away from the clear disparities in our nation’s schools, which relegate the black and brown to classrooms led by the least experienced teachers, we tell them this. Every time Bill O’Reilly pontificates about “black culture” and every time Barack Obama tells black men to be better fathers, we tell them this: that they are uniquely flawed, uniquely pathological, a cancerous mass of moral decrepitude to be feared, scorned, surveilled, incarcerated and discarded. The constant drumbeat of negativity is so normalized by now that it forms the backdrop of every conversation about black people held in white spaces when black folks themselves are not around. It is like the way your knee jumps when the doctor taps it with that little hammer thing during a check-up: a reflex by now instinctual, automatic, unthinking.

And still we pretend that one can think these things—that vast numbers of us can—and yet be capable of treating black folks fairly in the workforce, housing market, schools or in the streets; that we can, on the one hand, view the larger black community as a chaotic maelstrom of iniquity, while still managing, on the other, to treat black loan applicants, job applicants, students or random strangers as mere individuals. That we can somehow thread the needle between our grand aspirations to equanimity as Americans and our deeply internalized biases regarding broad swaths of our nation’s people.

But we can’t; and it is in these moments—moments like those provided by events in Ferguson—that the limits of our commitment to that aspirational America are laid bare. It is in moments like these when the chasm between our respective understandings of the world—itself opened up by the equally cavernous differences in the way we’ve experienced it—seems almost impossible to bridge. But bridge them we must, before the strain of our repetitive motion disorder does permanent and untreatable damage to our collective national body.

_____

*Robin D.G. Kelley, “Slangin’ Rocks…Palestinian Style,” in Police Brutality: An Anthology, Jill Nelson, ed., (New York, W. W. Norton, 2000), 21-59.

Tim Wise is the author of six books on race, including White Like Me: Reflections on Race from a Privileged Son and Dear White America: Letter to a New Minority. His website is timwise.org and he tweets @timjacobwise.

Week of November 14, 2014

Letter to the Editor: Daily Hampshire Gazette/Amherst Bulletin

by Michael Burkart, Amherst Area NAACP Executive Committee member

In a letter published on November 4th, the author responded to Dr. Barbara Love’s talk about racism. The author claimed that “racists exist in minority cultures as well.” I agree that prejudice exists across all groups, and any individual is able to exercise it.

However, a key factor in the exercise of prejudice is whether it can be coupled with institutional power.

Consider the fact that the biggest difference between whites and blacks is our net worth. That is primarily driven by how much money we inherit. The biggest factor in wealth creation is the increased value of homes, which gets passed from one generation to the next among whites.

Housing segregation is a nation-wide fact for blacks and many Latinos. This reality was intentionally created by decisions made during the creation of suburbs. Banks (via “redlining”), national realty policy, governmental bodies (state, federal and local), “urban renewal” policy (which destroyed more housing than it created), and restrictive housing covenants (upheld by federal court rulings) created this segregation.

This restriction of wealth continues via predatory lending and mortgage discrimination. The Federal Reserve’s own study in 2010 states: “Even within the same income range, blacks and Latinos experience much higher denial rates than whites and Asians. For example, black borrowers earning from $91,000 to $120,000 faced a denial rate that was two times higher than the denial rate for whites in that income bracket.” (p. 10)

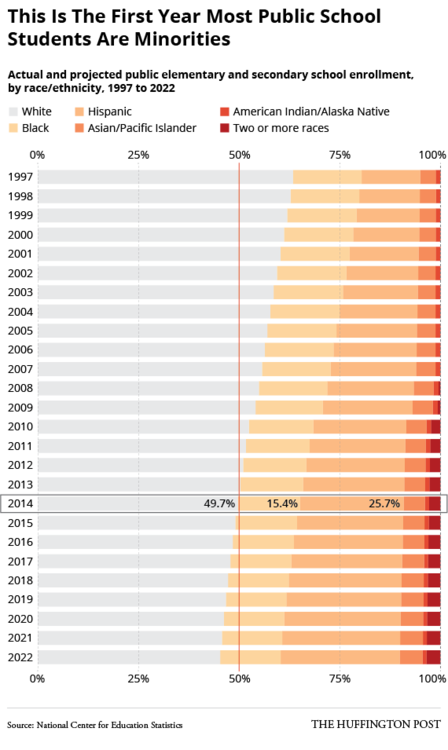

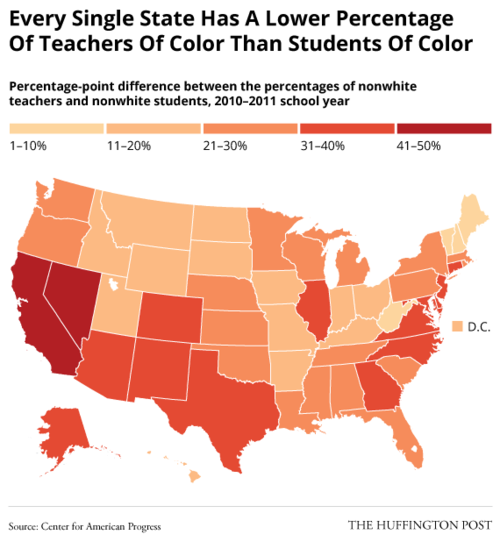

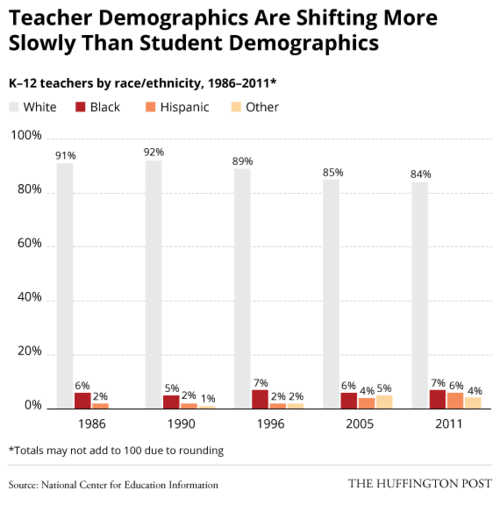

School de-segregation resulted in the firing of black teachers and administrators. Today, 90% of public school teachers and administrators are white.

Racism is the term typically used to refer to this coupling of prejudice plus power. I challenge anyone to show how whites are victimized by this kind of institutional power.

Week of September 15, 2014However, a key factor in the exercise of prejudice is whether it can be coupled with institutional power.

Consider the fact that the biggest difference between whites and blacks is our net worth. That is primarily driven by how much money we inherit. The biggest factor in wealth creation is the increased value of homes, which gets passed from one generation to the next among whites.

Housing segregation is a nation-wide fact for blacks and many Latinos. This reality was intentionally created by decisions made during the creation of suburbs. Banks (via “redlining”), national realty policy, governmental bodies (state, federal and local), “urban renewal” policy (which destroyed more housing than it created), and restrictive housing covenants (upheld by federal court rulings) created this segregation.

This restriction of wealth continues via predatory lending and mortgage discrimination. The Federal Reserve’s own study in 2010 states: “Even within the same income range, blacks and Latinos experience much higher denial rates than whites and Asians. For example, black borrowers earning from $91,000 to $120,000 faced a denial rate that was two times higher than the denial rate for whites in that income bracket.” (p. 10)

School de-segregation resulted in the firing of black teachers and administrators. Today, 90% of public school teachers and administrators are white.

Racism is the term typically used to refer to this coupling of prejudice plus power. I challenge anyone to show how whites are victimized by this kind of institutional power.

Multiculturalism Is Not An Assembly (or unit, class project, or lesson plan) by Amos Wolf Levy, Amherst Regional High School graduate

I’m a grad student at Duquesne, currently taking the course “Social Justice in Educational Settings.” For this class, I’m reading “Why Race and Culture Matter In Our Schools” by Tyrone C. Howard. As I think through Howard’s evidence and arguments, I can’t help but reflect on the successes and failures of my own culturally-responsive education, growing up in Amherst, Massachusetts in the 1990s.

If you've ever visited, you know that Amherst is a bastion of liberalism, and we’re proud of it. We were also proud of the multicultural appreciation that pervaded our school curricula. In elementary school assemblies I heard the West African legends of Anansi the Spider, and listened to the booming language of Congolese talking drums. In middle school, I watched athletic Chinese sword dances, listened to pan flute bands from the Andes. In high school, I played in a steel drum ensemble, and read Zora Neil Hurston, Richard Wright, Ralph Waldo Ellison, and Langston Hughes. I was taught to appreciate cultural differences. Every culture had something wonderful to celebrate. I felt good that we were so progressive and inclusive. Too bad it was a facade. This past year, it came crashing down.

Amherst Regional High School high school teacher Carolyn Gardener is no longer teaching her math class. This past school year she was targeted in three incidents of racist graffiti and a racist “prank letter” which included threats of gun violence. She’s currently on school district payroll, but Superintendent Maria Geryk has not yet announced Gardener’s new position. Geryk recently missed a large town forum about racism and education, organized by local radio station WHMP. In explaining her absence, Geryk, and fellow-no-show Town Manager John Musante, focused on their educational equity initiative. “We are focused on moving forwards with the Amherst Together initiative which is built on positive, forward thinking action. The positive momentum that is currently developing is central to the success of Amherst Together and for a strong community.” Launched earlier this summer, the initiative centers around a newly created position, “Media & Climate Communications Specialist” which who will work on “building equity in Amherst through community collaboration.”

Geryk is insistent on looking forwards to the future, but leading activists are bringing attention to historic trends of racism across the district. Concerned parents and social justice allies point to racial discrepancies in rates of school discipline as important evidence of systemic problems. In 2013, students of color were more than twice as likely to be disciplined than their white classmates. 1 in 14 black students was disciplined. 1 in 9 Latino students was disciplined. Amongst white students, only 1 in 33 was disciplined. Additionally, there are academic achievement gaps. Students of color enroll much less frequently in honors and AP level courses than their white classmates. Amherst Area NAACP President Kathleen Anderson addressed these issues in an open letter “To Our Amherst Community”:

What is happening to our students, all of our students, in our Amherst schools displays systemic racial and class bias not isolated, unrelated incidents. And, over the years our ARHS students of color and white students have documented such practices. As Amherst students continue their education from elementary to high school our district they will continually be taught nearly all topics and subjects from a [favorable to] Eurocentric perspective. Students will witness their mostly white teachers more harshly disciplining their classmates of color for the same or similar behaviors the same white teacher will ignore in white students. Our district has over a decade of data documenting this behavior on the part of our educators. In this situation students of color are at a definite power imbalance to object to this frequent and consistent discrimination and in fact may be disciplined for objecting. All the while our white students are observing and learning from the examples adults present to them. These behaviors model to future adults who then feel empowered to continue perpetuating habits of race and class bias among next generations. This creates a hostile and unsafe situation for all of our kids.

Concerned parents and allies have campaigned for decades for stronger action. As administrators try to address charges of systemic racism and classism, the rallies, protests, editorials, and continue to grow.

This mounting crisis points to the failure of the multicultural curriculum I knew growing up. This does not mean that we should do away with multicultural units and assemblies. We need to recognize that multicultural curriculum alone is not an effective response to systemic racism. At worst, these lessons become token political correctness. In sixth grade, humorist Dave Barry’s satirical history of the United States was one of my favorite books. In the book, each chapter includes the sentence, “women and minorities also made many important contributions during this time period.”

We need to change the way that teachers are relating to students of color. It’s tempting to identify dysfunction within communities of color as the reason for the problems. This is what Howard calls a cultural deficit paradigm. Researchers and theorists popularized this idea in the mid-20th century, pointing to poverty and limited cultural capital as the roots of poor student performance. Howard argues that this paradigm supports color-blindness and color-muteness, keeping educators from appreciating the cultural resources of communities of color. It also absolves educators of their responsibility to bridge cultural divides. Howard suggests that schools have a much larger role in affecting the performance and behavior of students than previously appreciated. “The contention is that while there are definitely students across all racial and ethnic groups who possess various cognitive, social, and emotional challenges, the over-representation of certain groups among those identified as such raises questions about how practitioners make judgments, and what role, if any, cultural misunderstandings and racial beliefs and attitudes may play in the decision-making process.” (Howard, pg. 22)

As the diversity of our student populations increase it become more and more vital that we successfully address the racial achievement gap. “If current achievement gaps continue over the next several decades, an increasing proportion of the nation’s citizens will be severely undereducated and ill prepared to compete in a global economy.” (Howard, pg 35) The shifting demographics of Amherst reflect this change. Students of color are rapidly becoming the majority filling classrooms. Last years high school class was 38.7% students of color, and last year’s kindergarten class was 55% students of color.

The tanning of schools does not bring with it an inevitable change in racial attitudes. White teachers, staffers, and administrators make up 82% of the Amherst school district payroll. These teachers need to learn to bridge cultural divides to successfully teach their students of color. Howard calls this “the demographic divide, wherein teachers face the reality that they are most likely to come into contact with students from cultural, ethnic, linguistic, racial, and social class backgrounds different from their own.” (Howard, pg 40)

During my thirteen years in the Amherst schools, I do not regret a single multicultural assembly that I attended, Harlem renaissance author that I read, or non-American culture that I studied. In fifth grade we watched the entire first two seasons of the TV show Roots and discussed the terrors of slavery. I celebrate this willingness to address injustices and colonialism early and often. However, it’s vital to recognize that curriculum enrichment alone will not reverse trends of racism in our schools. Small steps will not work. We need comprehensive and strategic approaches to closing the racial achievement gap, and these strategies need to be rooted in through evaluation and community accountability. It’s time to recognize the scope and importance of closing the racial achievement gap and take comprehensive steps to reach a solution.

Bibliography:

Anderson, Kathleen. “To Our Amherst Community” http://amherstnaacp.blogspot.com/. Accessed 9/8/14

Barry, Dave. Dave Barry Slept Here. Ballantine Books. New York. 1997

Howard, Tyrone C. Why Race and Culture Matter In Schools. Teachers College Press, New York . 2010

Lederman, Diane. “When Amherst Regional High School begins Thursday, Carolyn Gardner will not be teaching math” www.masslive.com. August 27, 2014

Lederman, Diane. “Amherst community members address racism without town and school officials in WHMP forum on Town Common“ www.masslive.com. Published August 21, 2014

Staffing Data by Race, Ethnicity, Gender by Full-time Equivalents (2013-14). Mass.gov. Accessed 9-11-14

2013-14 Amherst Regional Highschool Enrollment Data. Mass.gov. Accessed 9-11-14

2012-13 Student Dicipline Data Report. Mass.gov. Accessed 9-11-14

Graphs and infographics from:

Klein, Rebecca. “A Majority Of Students Entering School This Year Are Minorities, But Most Teachers Are Still White” Huffington Post. Accessed 9/12/14

Klein, Rebecca. “A Majority Of Students Entering School This Year Are Minorities, But Most Teachers Are Still White” Huffington Post. Accessed 9/12/14

Week of August 18, 2014

A MOTHER’S WHITE PRIVILEGE

What if my son was black? How would you see this picture?

As the ongoing events in Ferguson, Missouri show us, America’s racial tensions didn’t disappear when George Wallace backed down from the schoolhouse door. Dr. King didn’t wave a magic wand, and we never got together to feel all right. White America remembers this at ugly flashpoints: the Rodney King beatings, the OJ Simpson trial, the Jena Six, Trayvon Martin’s death. White America recoils in horror not at the crimes – though the crimes are certainly horrible. It’s not the teenagers gunned down, the police abuse, the corrupt trials. It’s this: at these sudden, raw moments, in these riots and demonstrations and travesties of justice, White America is forced to gaze upon the emotional roil of oppression, the anger and fear and deep grief endemic to the Black American experience. Black America holds up a mirror for us.

And white America is terrified to look.

To admit white privilege is to admit a stake, however small, in ongoing injustice. It’s to see a world different than your previous perception. Acknowledging that your own group enjoys social and economic benefits of systemic racism is frightening and uncomfortable. It leads to hard questions of conscience may of us aren’t prepared to face. There is substantial anger: at oneself, at the systems of oppression, and mostly at the bearer of bad news, a convenient target of displacement. But think on this.

I have three sons, two years between each. They are various shades of blond, various shades of pinkish-white, and will probably end up dressing in polo shirts and button downs most of the time. Their eyes are blue and green. Basically, I’m raising the physical embodiment of The Man, times three. The White is strong in these ones.

Clerks do not follow my sons around the store, presuming they might steal something.

Their normal kid stuff – tantrums, running, shouting – these are chalked up to being children, not to being non-white.

People do not assume that, with three children, I am scheming to cheat the welfare system.

When I wrap them on my back, no one thinks I’m going native, or that I must be from somewhere else.

When my sons are teenagers, I will not worry about them leaving the house. I will worry – that they’ll crash the car, or impregnate a girl, or engage in the same stupidness endemic to teenagers everywhere.

I will not worry that the police will shoot them.

If their car breaks down, I will not worry that people they ask for help will call the police, who will shoot them.

I will not worry that people will mistake a toy pistol for a real one andgun them down in the local Wal-Mart.

In fact, if my sons so desire, they will be able to carry firearms openly.Perhaps in Chipotle or Target.

They will walk together, all three, through our suburban neighborhood. People will think, Look at those kids out for a walk. They will not think, Look at those punks casing the joint.

People will assume they are intelligent. No one will say they are “well-spoken” when they break out SAT words. Women will not cross the street when they see them. Nor will they clutch their purses tighter.

My sons will never be mistaken for stealing their own cars, orentering their own houses.

No one will stop and frisk my boys because they look suspicious.

My boys can grow their hair long, and no one will assume it’s a political statement.

My boys will carry a burden of privilege with them always. They will be golden boys, inoculated by a lack of melanin and all its social trapping against the problems faced by Black America.

For a mother, white privilege means your heart doesn’t hit your throat when your kids walk out the door. It means you don’t worry that the cops will shoot your sons.

It carries another burden instead. White privilege means that if you don’t school your sons about it, if you don’t insist on its reality and call out oppression, your sons may become something terrifying.

Your sons may become the shooters.

Like Manic Pixie Dream Mama on Facebook to read more about social justice issues, race, and attachment parenting.

Week of July 14, 2014

Caught in a time warp: The NAACP’s Will Singleton says Pittsfield’s municipal government doesn't reflect the community’s changing demographics

|

| What if my son was black? How would you see this picture? |

As the ongoing events in Ferguson, Missouri show us, America’s racial tensions didn’t disappear when George Wallace backed down from the schoolhouse door. Dr. King didn’t wave a magic wand, and we never got together to feel all right. White America remembers this at ugly flashpoints: the Rodney King beatings, the OJ Simpson trial, the Jena Six, Trayvon Martin’s death. White America recoils in horror not at the crimes – though the crimes are certainly horrible. It’s not the teenagers gunned down, the police abuse, the corrupt trials. It’s this: at these sudden, raw moments, in these riots and demonstrations and travesties of justice, White America is forced to gaze upon the emotional roil of oppression, the anger and fear and deep grief endemic to the Black American experience. Black America holds up a mirror for us.

And white America is terrified to look.

To admit white privilege is to admit a stake, however small, in ongoing injustice. It’s to see a world different than your previous perception. Acknowledging that your own group enjoys social and economic benefits of systemic racism is frightening and uncomfortable. It leads to hard questions of conscience may of us aren’t prepared to face. There is substantial anger: at oneself, at the systems of oppression, and mostly at the bearer of bad news, a convenient target of displacement. But think on this.

I have three sons, two years between each. They are various shades of blond, various shades of pinkish-white, and will probably end up dressing in polo shirts and button downs most of the time. Their eyes are blue and green. Basically, I’m raising the physical embodiment of The Man, times three. The White is strong in these ones.

Clerks do not follow my sons around the store, presuming they might steal something.

Their normal kid stuff – tantrums, running, shouting – these are chalked up to being children, not to being non-white.

People do not assume that, with three children, I am scheming to cheat the welfare system.

When I wrap them on my back, no one thinks I’m going native, or that I must be from somewhere else.

When my sons are teenagers, I will not worry about them leaving the house. I will worry – that they’ll crash the car, or impregnate a girl, or engage in the same stupidness endemic to teenagers everywhere.

I will not worry that the police will shoot them.

If their car breaks down, I will not worry that people they ask for help will call the police, who will shoot them.

I will not worry that people will mistake a toy pistol for a real one andgun them down in the local Wal-Mart.

In fact, if my sons so desire, they will be able to carry firearms openly.Perhaps in Chipotle or Target.

They will walk together, all three, through our suburban neighborhood. People will think, Look at those kids out for a walk. They will not think, Look at those punks casing the joint.

People will assume they are intelligent. No one will say they are “well-spoken” when they break out SAT words. Women will not cross the street when they see them. Nor will they clutch their purses tighter.

My sons will never be mistaken for stealing their own cars, orentering their own houses.

No one will stop and frisk my boys because they look suspicious.

My boys can grow their hair long, and no one will assume it’s a political statement.

My boys will carry a burden of privilege with them always. They will be golden boys, inoculated by a lack of melanin and all its social trapping against the problems faced by Black America.

For a mother, white privilege means your heart doesn’t hit your throat when your kids walk out the door. It means you don’t worry that the cops will shoot your sons.

It carries another burden instead. White privilege means that if you don’t school your sons about it, if you don’t insist on its reality and call out oppression, your sons may become something terrifying.

Your sons may become the shooters.

Like Manic Pixie Dream Mama on Facebook to read more about social justice issues, race, and attachment parenting.

Week of July 14, 2014 |

| Members of the Berkshire County NAACP, with Will Singleton in center in navy sweater and drawstring pants. |

WILL SINGLETON DIDN’T know what to make of it. The retired Pittsfield native had been back in town for years, and he never saw any African Americans working in City Hall. People of color account for nearly 15 percent of the population in this western Massachusetts city of 45,000, but they are largely invisible in city government. Only 4 percent of the city’s workforce is black, Hispanic, or Asian.

The 70-year-old Singleton grew up in Pittsfield. He has fond memories of spending time at the Boys Club, the YMCA, and the region’s lakes in the summer. He went on to a career in education, retiring more than a decade ago as the superintendent of a New York school district. Seven years ago, Singleton’s siblings suggested the widower return to Pittsfield to care for their elderly father, a retired General Electric employee. What Singleton found was a city caught in a time warp. Read the rest of the article by clicking here.

The 70-year-old Singleton grew up in Pittsfield. He has fond memories of spending time at the Boys Club, the YMCA, and the region’s lakes in the summer. He went on to a career in education, retiring more than a decade ago as the superintendent of a New York school district. Seven years ago, Singleton’s siblings suggested the widower return to Pittsfield to care for their elderly father, a retired General Electric employee. What Singleton found was a city caught in a time warp. Read the rest of the article by clicking here.

Week of June 2, 2014

Time to find the real criminals at ARHS

By Agnes Zsigmondi

Watching the latest School Committee meeting on TV, I found out that the police interrogated several Crocker Farm School parents in connection with a recent lockdown. They continued their investigation even after the reason (mistaken identity) was clear to all and it was obvious that the parents had nothing to do with the incident. I wonder if this is the best way for our law enforcement to use their resources. It seems that their attention and time would be better used to find the criminals who commit the racial harassments over and over at the high school. If the police who are trained to find seasoned criminals can not solve these crimes, it is time to bring the FBI in to get to the end of this problem and assure the town that our teachers can be safe from racist attacks. We constantly talk about safety in the schools. How can anyone, especially students feel safe in a building knowing that even their teachers can not be protected from these heinous crimes in our schools?

Watching the latest School Committee meeting on TV, I found out that the police interrogated several Crocker Farm School parents in connection with a recent lockdown. They continued their investigation even after the reason (mistaken identity) was clear to all and it was obvious that the parents had nothing to do with the incident. I wonder if this is the best way for our law enforcement to use their resources. It seems that their attention and time would be better used to find the criminals who commit the racial harassments over and over at the high school. If the police who are trained to find seasoned criminals can not solve these crimes, it is time to bring the FBI in to get to the end of this problem and assure the town that our teachers can be safe from racist attacks. We constantly talk about safety in the schools. How can anyone, especially students feel safe in a building knowing that even their teachers can not be protected from these heinous crimes in our schools?

Then, to "Opinion" Daily Hampshire Gazette:

A Sharpie Does Not Slash Tires

"I was reading your guest column "Lightening up our Amherst Angst" by a high school senior with great disappointment. The letter suggest that our community should not be offended so much by the racial attacks on our teacher. "Maybe an angry kid with a sharpie is just an angry kid with a sharpie" the letter suggests. The acts of slashing a teacher's tires, sawing the leg of someone's chair, so it would collapse when one set on it are not done with a sharpie. Although the additional threatening and demeaning words and notes addressing a respectable teacher at the high-school are, they are not just offensive but frightening as well. They are hate speech and racial harassment and are punishable crimes weather done by children or grownups. Students can not feel safe in a school knowing that even their teacher can not be protected by bullying."

Week of May 19, 2014

“Talking White”: How Racial Superiority Seeps Into Our Language

by Christopher Peck

Racism is still alive, but some wish to declare it dead. Intellectuals, politicians and TV personalities discuss racial oppression like it’s an endangered species. The denial runs deep; and its roots cling to the foundation of our society: language.

Whenever I ask another white person how they would define racism I get a vague, disjointed and vastly different answer each time. For some, even mentioning racial difference is taboo. Others say racism is illustrated in separate water fountains and sitting in the back of the bus. It happened a “long time ago” and we’ve moved on. Others rant emphatically that racism is when white people are “passed over for a job they gave to a less qualified black guy.” I firmly believe that’s the most persistent impediment to racial equity and justice. Nobody knows what racism is.

We should not lose sight of the symbolic weight that language carries. Whoever controls language holds the power—the power to possess the right answers, to declare oppositions wrong and to alter and diminish the meaning of others’ experiences. This leads directly to the delusion and entitlement of white students. They respond defensively when their worldview is questioned and deflect responsibility because their superiority has been validated by their education. Because we as a society have failed to define racism for them they not only refuse to acknowledge the impact of race, they reinforce the cycle. It represents our nation’s attitudes of ignorance and disregard towards the plight of people of color as a whole that we do not have an impenetrable meaning attached to the word racism. And yet, there are symbols sustaining white supremacy, loaded with racist implications engrained in our everyday speech.

As a white man, I won’t pretend that I hold all the answers. Instead I’ve chosen to develop a compassionate ear. I’ve spent the latter third of my life listening to testimonies from people of color. Unsurprisingly, they have profound things to say about how growing up with darker skin has impacted them across all institutions. While their experiences may differ, there’s agreement on the source of their struggle. The People’s Institute For Survival and Beyond has generated this definition.

Racism—n. Racial prejudice + institutional power. A system of oppression maintained by institutions and cultural ‘norms’ that exploit, control, and oppress People of Color in order to maintain a position of social supremacy and privilege for white people.

It is important to emphasize then that although a white person can be discriminated against individually based on their race, racism is specifically the upholding of white supremacy at the expense of people of color as a group.

The next definition I will share from the People’s Institute is one regarding Internalized Racial Superiority:

n. The acceptance of and acting out of a superior definition, rooted in the historical designation of one’s race. This process of empowerment and access expresses itself as unearned privileges, access to institutional power and invisible advantages based upon race.

As I alluded to, language becomes like the post office worker for delivering this “superior definition.” And our school system has become the USPS of racist codes.

Subtle racist codes were rampant during my high school days and still are from what I’ve observed. As someone socialized as white, I understand how white people are conditioned to not think of themselves as “white.” Race was a non-issue, until a person of color brought it up. My teachers would use the term “race card” as a way of “stopping conflict.” Any racial grievance was unsubstantiated.

Voices from the Community

While this is not yet a newspaper article it is written by Jared Schy, a graduated UMass, Amherst student, who wanted to share his thoughts:

I was reflecting today and in recent weeks...I'm the type of person public "education" was designed for, white, male, upper middle class---they nearly kept me insulated enough to unquestioningly become a member of the ruling, or at least managing class, until one teacher had the foresight to suggest reading some books on poverty, which in my hyper insulated Newton existence, opened my eyes to a lot of things I'd never considered before. And actually, it was taking the SAT's for the second time--can you tell this is an upper middle class town?--in Somerville opposed to Newton that gave me the concrete context to open my eyes and awaken me to the stark differences in just about everything only 11 miles away...

But school was supposed to "work" for me. I see myself in the curriculum and history, I am undeservedly praised for things students of color, girls, and poor/working class kids are likely not; I am not treated as a suspect or a criminal and teachers look the other way should I take part in any "suspect" activity, etc, etc, etc... But let me say honestly what I feel I about my experience in school looking back... IT WAS SO F#%+ING BORING!!! And I can honestly say beyond reading, I learned little of any value beyond basic study habits. And despite our school being 'ram you down the throat college prep savvy (kill me)', I hardly learned how to write until sophomore or junior year of college.